The most dangerous bird in the world

Beware the cassowary?

The 2019 headline Cassowary kills man near Alachua made the cassowary famous as the world’s most dangerous bird. But what is a cassowary? Why are they dangerous, and are they really the most dangerous bird in the world? In this edition of Mortal Combat, we will investigate the deadly beauty of the murder bird.

Dinosaurs never left. The asteroid that hit the Yucatan Peninsula 66 million years ago caused a global catastrophe, a mass extinction of animal life that is estimated to have wiped out over 70% of life on Earth. Although the ‘classic’ dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops went extinct, some dinosaurs survived. Today, we are surrounded by tens of thousands of species of dinosaurs. I encountered one this morning, who watched me from a tree as I walked to the library. These small, feathered dinosaurs, which are most commonly called birds, diverged from their larger cousins over a hundred million years prior to the end of the Cretaceous period. Although familiar birds like chickens, sparrows, and turkeys don’t match the stereotypical giant, scaly dinosaur, birds are dinosaurs all the same.

The earliest fossil bird Archaeopteryx was found in an 150 million year old lagoon in Germany, showing that birds diverged from their dinosaurian cousins long before the asteroid struck. Traits that we associate with birds, including feathers, wish-bones, lightweight bones, and nest building are all heirlooms inherited from dinosaurian ancestors. The earliest birds retain teeth, bony tails, and long fingers; dinosaurian traits that were lost over tens of millions of years of evolutionary history. Although the fundamental science on this has been settled for decades, I have encountered people who actively deny that birds are dinosaurs.

Figure (above): The Berlin specimen of Archaeopteryx lithographica, the earliest known bird. Note the feathered wings, bony tail, and elongate, clawed fingers. The feathers are preserved as imprints in the muddy matrix surrounding the arms, tail, and body. Fossils like Archaeopteryx show how birds evolved from dinosaurian ancestors. Photo from Wikipedia user H. Raab. No changes made, License.

I think that one reason people may believe that birds aren’t dinosaurs comes down to cultural perception. Although the majority of dinosaurs were not giant, the most common image of dinosaurs in our culture are the tyrannosaurs and raptors of Jurassic Park. My perspective may be biased by growing up in rural Michigan, where the most commonly encountered birds are sparrows, cardinals, and other small, fat, mostly harmless little birds. The birds I encountered growing up prefer to hide or fly away from potential predators. Birds therefore have a reputation as being somewhat cowardly, to the point that calling someone a chicken is an insult. Like a lot of cultural stereotypes, the idea that chickens or birds in general are cowardly is incorrect. A malevolence brews beneath the feathered exterior. The meanest animals I ever encountered are market chickens (meaning being raised for their meat), which would attack me on sight no matter what. Those mean chickens are not an exception.

A lot of birds are nasty, violent animals, although most are not particularly dangerous to humans due to small size and fragility. Flight imposes strict physical limitations on the size and weight of most birds, hence why the majority are small and have light, hollow bones. A group of birds called the ratites have broken free of these restrictions in being flightless. The ratites include the largest living bird, the ostrich, along with much larger extinct birds. The presence of vestigial wings in ratites indicates that they evolved from flighted birds that adapted to niches that do not require flying. Ratites include the largest birds to ever live, including the extinct elephant birds of Madagascar and the moas of New Zealand, which tower at ~3.6 m (12 ft tall). Sadly, because these giants are extinct, from human influence on their delicate island ecosystems, we know very little about their behavior.

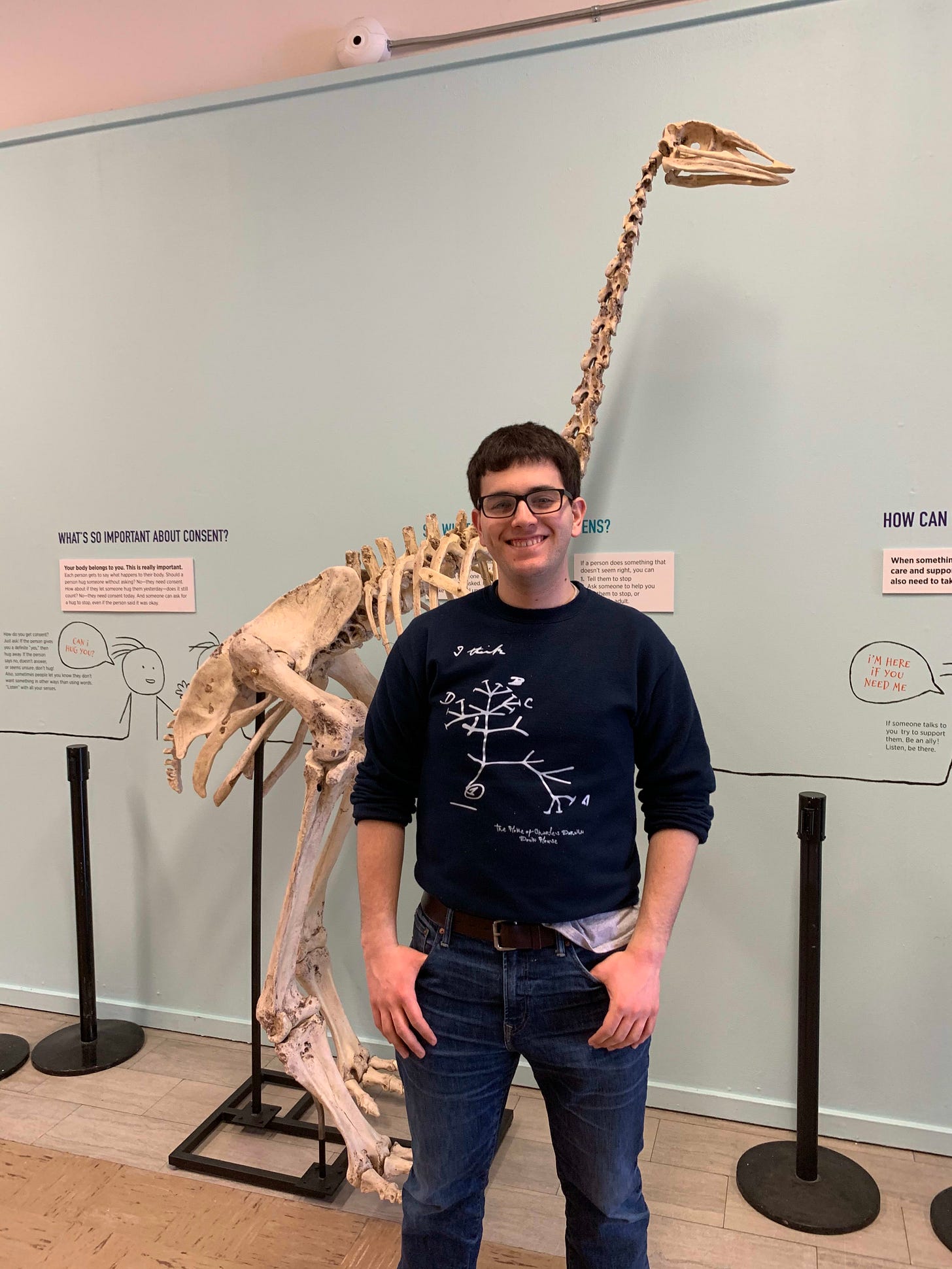

Figure: Me (just under 6 ft tall) in the foreground of a mounted skeleton of a moa at the Michigan State Museum. This does not do it justice, they are truly giant birds.

Today, ratites include South American rheas, African ostriches, Australian emus, the kiwis of New Zealand, and the cassowaries of Australia and New Guinea. Of the ratites, the cassowary has the most dangerous reputation, declared the deadliest bird in the world for good reason. All three living species of cassowary have reportedly attacked and killed humans. However, the most infamous is the southern cassowary, Casuarius casuarius, which can grow up to 1.7 m tall and weigh 70 kg. Southern cassowaries live in tropical forests in Australia and New Guinea. The cassowary is a drop-dead beauty, with mostly black feathers, a blue head, and an enlarged bony crest. The bony crest or ‘casque’ may look like a helmet, but it is quite fragile and likely serves for display purposes only. The arms are tiny, vestigial wings that are not easily observed. Cassowaries stand on stout, long legs and three-toed feet that are reminiscent of the predatory dinosaurs of the Mesozoic. The medial (closest to the midline) toe of each foot bears an elongate, sharp claw. Although the enlarged toe claw in cassowaries bears some resemblance to the enlarged, scythe-like ‘killing claw’ of dromaeosaur (=raptor) dinosaurs, it serves primarily as a defensive weapon. Cassowaries subsist primarily on fruit, and if left to their own devices will use their claws to dig through the leaf litter for food. If bothered or threatened, however, cassowaries will deliver powerful kicks that can maim or disembowel potential threats. In a perfect world, cassowaries and humans would avoid each other and this article wouldn’t exist. Sadly, we don’t live in a perfect world.

Figure (above): The southern cassowary. Note the long, powerful legs and the enlarged bony ‘casque’ on the head. The wings are so small you can’t see them! Photo by Graham Winterflood, sourced from Wikipedia. No changes made, License.

Figure (above): Mounted cassowary skeleton (left) showing the long legs, fragile bony ‘casque’, and the tiny, vestigial wings (check the front of the rib cage area). Specimen on display at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, photo by Jack Stack.

Interactions between humans and cassowaries are relatively common and hundreds of attacks have occurred. A guide I found on caring for cassowaries as zoo animals notes that they are immensely strong and need to be handled with caution. Sadly, cassowaries and humans overlap and interact on a regular basis, with interactions often being antagonistic. We will focus on Queensland, Australia, where we have the most available data by far. Christopher Kofron surveyed 221 reported attacks in a 1999 study, 150 of which were on people. Cassowaries are also known to attack dogs, windows, and rarely domestic horses and cows. Of the surveyed attacks in Queensland, only one was fatal. Two boys made the unfortunate decision to attack a cassowary with clubs, and one of them passed away from wounds sustained from the animal’s defensive reaction. Other serious attacks resulting in major injuries were reported, as a cassowary can deliver extremely powerful kicks and even jump on top of people who fall down. The 2019 Florida case, the second fatal attack I could find direct documentation for (although other species are thought to have attacked and killed people) involved an elderly man falling down and being jumped on and kicked. The cassowary in that instance was a pet rather than a wild individual. Clearly, cassowaries are powerful animals that are capable of seriously injuring or killing people.

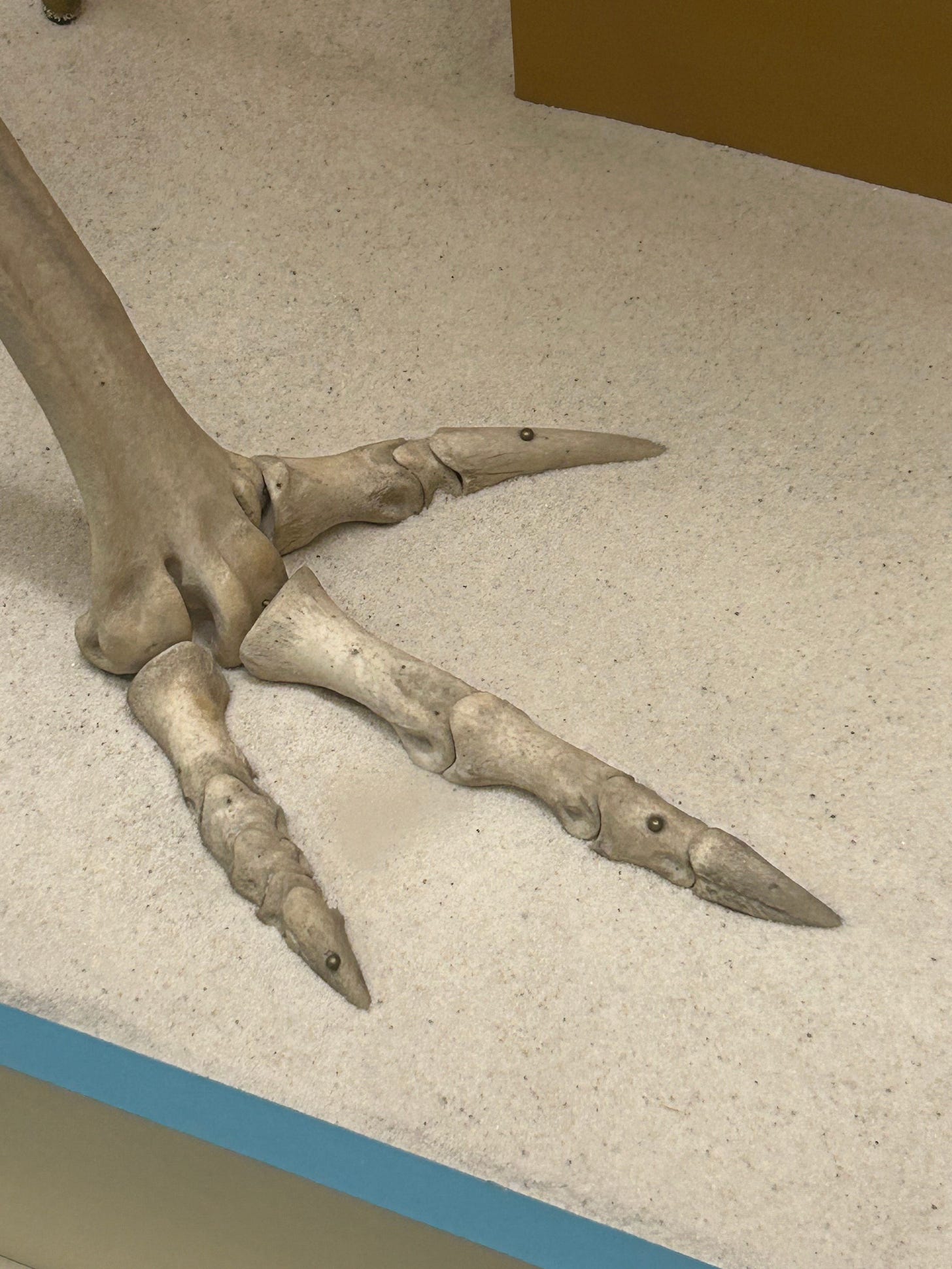

Figure (above): The foot of the southern Cassowary on display at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Note the enlarged claw on the toe farthest from you, which in-life bears a sharp sheath. Photo by Jack Stack.

The more I read about them, the more I think cassowaries have a somewhat unfair reputation. Almost three quarters of cassowary attacks in Queensland were by animals that had been fed by humans, and were expecting or soliciting food. Other attacks were in self defense, defending chicks, eggs, or a food source. Even though cassowaries are dangerous, it is unfair to call them deadly without noting the human side of the equation. Unexplained or unprovoked attacks are rare, the vast majority result from people feeding wild and very powerful prey animals or keeping them as pets. Feeding wild animals like cassowaries alters their behavior, causing them to seek food from other people and leading to dangerous situations, as happened in June of this year in Queensland, Australia. Large, undomesticated wild animals are very dangerous to keep as pets or feed. Even animals that are herbivorous like cassowaries can be dangerous to themselves or to you because of their size, strength, and potential reaction to danger. If you were ever planning on feeding or God-forbid purchasing a cassowary, do not.

Cassowaries are rightly considered dangerous. As we have seen, they are large, strong animals that can and have killed people. However, we see that violent behavior is almost always atypical, resulting from human feeding or being kept as pets. So while cassowaries should be avoided except by zoo professionals, the burden is on us. We can appreciate and conserve cassowaries and other ratites for future generations by not interfering with them and not making foolish decisions that lead to injuries or death. We have the power to create a world where we keep people safe and conserve large, extraordinary animals like the cassowary. Let us learn from the tragedies of the past and create a better future for ourselves and the large dinosaurs we share the planet with.

Sources and further reading:

Benton, M.J., 2014. Vertebrate Palaeontology. John Wiley & Sons.

Biggs, J. and Zoo, C.T., 2013. Captive Management Guidelines for the Southern Cassowary. Casuarius casuarius johnsonii. Cairns Tropical Zoo.

Grzimek, B., Hutchins, M., Schlager, N., Olendorf, D., McDade, M. C., & American Zoo and Aquarium Association. (2002). Grzimek’s Animal life encyclopedia (2nd ed). Gale.

Jablonski, D., & Chaloner, W. G. (1994). Extinctions in the Fossil Record. Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences, 344(1307), 11–17. http://www.jstor.org/stable/56148

Kofron, C.P., 1999. Attacks to humans and domestic animals by the southern cassowary (Casuarius casuarius Johnsonii) in Queensland, Australia. Journal of Zoology, 249(4), 375–381.

Naish, D. and Perron, R., 2016. Structure and function of the cassowary's casque and its implications for cassowary history, biology and evolution. Historical Biology, 28(4), 507–518.

Richards B, June 2025: “Mother and Child Narrowly Escape the 'World's Most Dangerous Bird.' See Footage of the 'Close Encounter”. https://people.com/mother-child-narrowly-escape-worlds-most-dangerous-bird-cassowary-11761358.

Swirko C, April 2019: “Cassowary kills man near Alachua”. https://www.gainesville.com/story/news/local/2019/04/13/cassowary-kills-man-at-farm-near-alachua/5443887007/

Jesus Christ! Cassowaries are probably worse pets than even crocodilians (albeit crocodilians that are selectively bred to be pets, but still). Why are they being sold?

Also I suspect that the gradual increase in people denying birds being dinosaurs comes from confirmation bias, where they get all of their information from echo chambers feeding them desired info, 24/7.

I can’t believe anyone would keep a cassowary as a pet! I mean they’re beautiful animals, but what an awful thing to do.