I see dead fishes

Making a history of fishes for the 21st century

A principal goal of biology is to reconstruct the history of life on Earth. Since the inception of formal systematics in the 18th century, scientists have described the processes by which species change with time (evolution) and cease to exist (extinction). The knowledge that biological species, many of which are essential to the health, wealth, and culture of human society, can both change and die transforms systematics from an exercise in organization to an essential science of the 21st century. 21st century systematics uses evolution as an organizing principle, meaning that we reconstruct the evolutionary history of species of interest to name and describe the diversity of life on Earth. This diversity includes ourselves and our place among living things.

My goal is to bridge our knowledge of those species alive today with those that have gone extinct. Although extinct species are typically represented by fossils that are devoid of soft-tissue, genetic, and behavioral data, they provide a perspective on the deep time (hundreds of thousands or millions of years of history) that is essential to reconstructing evolutionary history. I study the ray-finned fishes (Actinopterygii) because they include one out of every two vertebrate species on Earth and have an excellent fossil record, making them ideal for building bridges between our knowledge of living and extinct species. Uniting data from living and extinct ray-finned fishes provides a window into early evolution of those groups alive today and the pattern of evolutionary history of Actinopterygii. Additionally, the methods used for fishes can be extended to other groups of organisms, whose fossil record may not be as complete.

In a study published this morning in the Anatomical Record, I examine the evolutionary history of ray-finned fishes in deep time with a novel dataset that samples both living and extinct groups. I expand on traditional methods in morphological phylogenetics by applying ontological reasoning, that is, using a unified vocabulary of vertebrate and ray-finned fish skeletons, to connect observations of living and fossil fishes. My work stands on the shoulders of dozens of brilliant scientists in the Phenoscape project, who worked tirelessly to create unified vocabularies for the vertebrate skeleton, for fishes, and who taught me these methods. The immediate practical advantage of ontological reasoning is the improved quality and comparability of systematic studies. With a common language of anatomy, it is easier for scientists to share observations and build a unified knowledge of the history of the group of interest. Ontologies also make anatomical data computable, meaning that complex information can be interpreted by machine learning and other advanced programs.

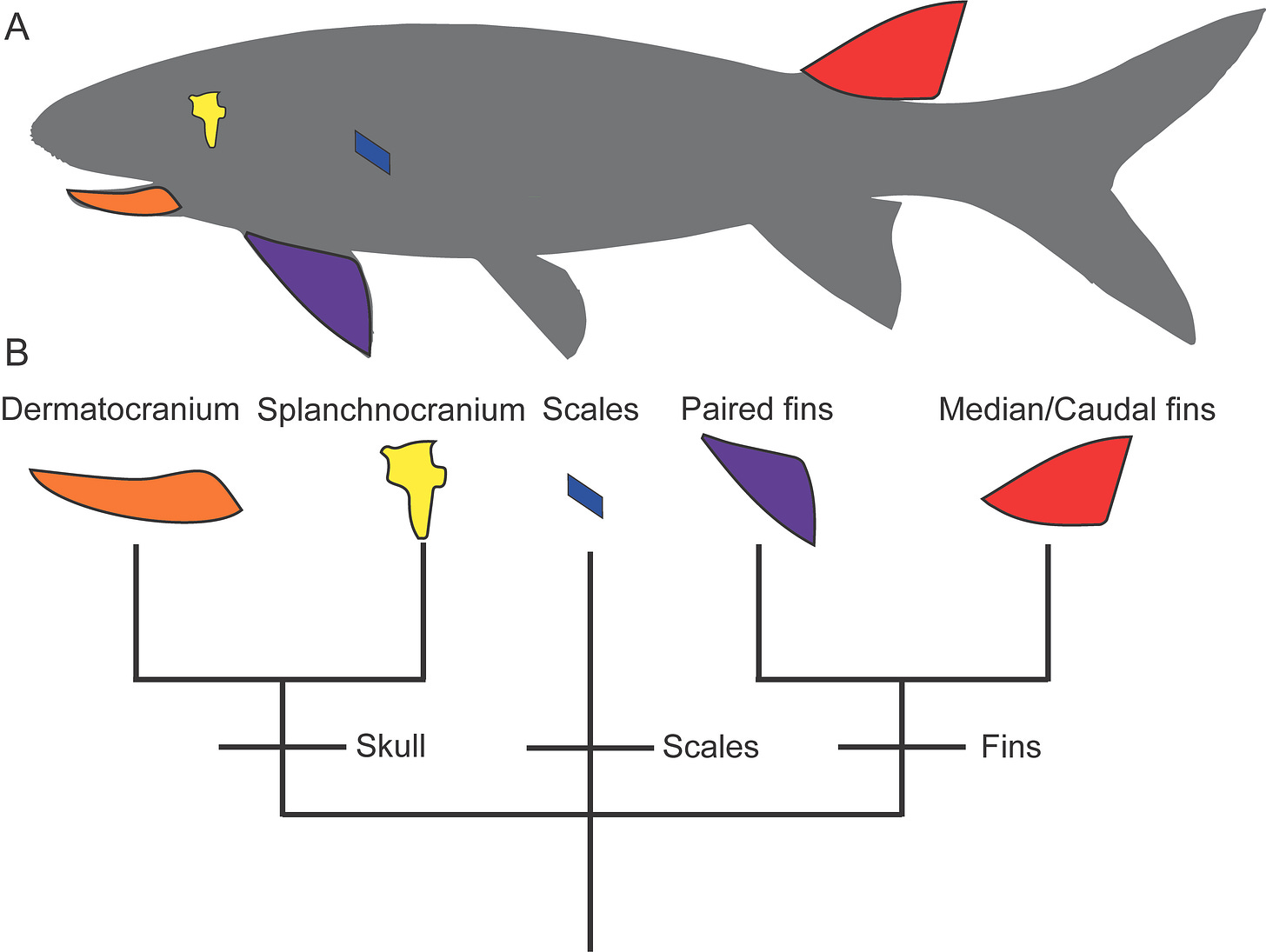

Above: Application of an ontology (an anatomical vocabulary with relationships between entities defined) to ray-finned fishes. Note that each region and part, and the relationships between them, are traceable and computable.

Ontological character construction also presents an opportunity to radically advance the study of the history of life. The biggest obstacle to the progress of the study of organisms from the fossil record is that researchers and datasets are largely disconnected from each other. Systematic studies of the morphology of say, ancient ray-finned fishes, are disconnected from studies of extant members of the group and other animals such as lizards or salamanders. My effort to connect studies of fossil and living ray-finned fishes is tiny when we consider the vast diversity of vertebrate groups. Domain experts are largely siloed within their group of interest, using different terms to refer to structures that are shared. Conferences such as the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology separate posters and talk sessions by systematic group, and lab groups are typically divided by what organism the principal investigator is trained in. With the development of unified ontologies for the vertebrate skeleton (Dahdul et al. 2012), we have the potential to build a network of systematic knowledge that could unite the work of all vertebrate systematists. We could build a network of knowledge that would allow any person, anywhere, to draw upon the learning and experience of tens of thousands of workers in an instant. One shared language of anatomy, connected by 21st century technology, would allow us to build together, rather than apart. Our shared knowledge could be used to build phylogenetic trees needed to model the evolution of form, ecology, and diversity across space and geologic time on an enormous scale. The work required to reach this point is gargantuan, as it would require experts from each sub-field to contribute, but the reward would be akin to a network of roads that unite a vast and diverse county. Information flow would be instant between domains, and knowledge would no longer be locked behind terminology.

Perhaps this vision seems fanciful, but it is written from a deep feeling of dread for the future of biology. The model of the taxonomist being an isolated, broom closet dwelling monk who alone carries the mantle of a group of interest, documenting their knowledge in obscure journals and in a language few can understand, threatens to drive our field to extinction in the 21st century. I fear a world a century from now where taxonomists are extinct, our knowledge lost because, even if our writing is saved, no living person can make heads or tails of our language. I fear a world where only the very few and the very privileged have access to the history of life. In this future world species go extinct without anyone to signal alarm, governmental and societal decisions are made without the guidance of experts in the group of interest, and quantitative research draws on multitudes of computer-generated datasets that are inaccurate, without anyone to notice the errors. We can avoid this doom by embracing the 21st century, not abandoning domain experts but uniting their knowledge in an interpretable, shareable, and computable form that will empower scholars, citizens, and students to make informed decisions and study the evolution of life on Earth. In this, I see a future where knowledge of the history of life is connected in a vast network, where centuries of effort are recorded and available to all, and new information is added daily by scientists, citizens, and governments to the benefit of society. In this world, systematists have avoided extinction by evolving our effort to study biodiversity.

My research efforts will continue to focus on the ray-finned fishes, past and present, to reconstruct their history in deep time. My goals are to understand the origin of those groups we have today, and to study how present species will respond to changes in the Earth system, both human-made and all-natural. I also seek to build a community of scientists and citizens alike who are invested in natural history. Through my writing, my teaching, and my research, I will work to bring the history of life into the 21st century and beyond for everyone.

Acknowledgements:

I would like to personally thank Drs. Wasila Dahdul, Katherine Corn, Sterling Nesbitt, Stocker, and Josef Uyeda for their support and assistance in making my research using ontologies possible.

References:

Dahdul, W.M., Balhoff, J.P., Engeman, J., Grande, T., Hilton, E.J., Kothari, C., Lapp, H., Lundberg, J.G., Midford, P.E., Vision, T.J. and Westerfield, M., 2010. Evolutionary characters, phenotypes and ontologies: curating data from the systematic biology literature. PLoS One, 5(5), p.e10708.

Dahdul, W.M., Balhoff, J.P., Blackburn, D.C., Diehl, A.D., Haendel, M.A., Hall, B.K., Lapp, H., Lundberg, J.G., Mungall, C.J., Ringwald, M. and Segerdell, E., 2012. A unified anatomy ontology of the vertebrate skeletal system. PloS one, 7(12), p.e51070.

Stack, J. (2025). An ontological morphological phylogenetic framework for living and extinct ray-finned fishes (Actinopterygii). The Anatomical Record, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.70090