Fish History 101

If success was a numbers game (and in some ways it is), the fish would be winning. There are more species of fishes than there are mammals, reptiles, birds, and amphibians combined. Traditionally, the formal study of the history of this vast diversity is called “paleoichthyology”. The central issue with this term is that it only covers studying fish fossils (paleontology) and studying living fishes (ichthyology). However, fishes are not just fossils or individual animals. Fishes are essential components of our society, our economy, and our world. Because of the importance of fish as food, as pets, and as sport, I think that we also need to consider human history, economics, and culture when studying the history of fishes. Therefore, fish history is the broad synthesis of the science of fishes and our interactions with them.

Learning fish history requires understanding some essential concepts in their biology. Think of these concepts as tools, like the hammer, nails, screwdrivers, pliers, and wrenches in your dad’s toolbox. As my father taught me, having a combination of tools, each suited for a certain task, is essential to achieving a broader goal. We need some basic tools if we want to break down complicated concepts and understand the deep and beautiful history of fishes. Otherwise, we would quickly become lost in the interconnected web of fish biology, scientific history, and the deep history of the Earth and its inhabitants.

The first tool is defining what is and what is not a fish. Although we could descend into a deep scientific debate over this subject, I will spare you the pedantic screed and provide a practical definition. I wrote our definition to draw upon features shared by species that have a common history to include living fishes and the wider diversity of extinct fishes. Namely, fishes are aquatic vertebrates whose ancestors never left the water. The shared history of being primarily aquatic has left its mark in the anatomical features and lifestyle of fishes. A fish is an aquatic, back-boned animal that propels itself through the water with fins and breathes through gills. Notably, our definition excludes a great many interesting creatures, including whales, dolphins, turtles, ducks (and other aquatic birds), frogs, crocodiles, and aquatic insects. We are also excluding every invertebrate you can think of that has the word “fish” in its name, such as starfish. This definition includes tens of thousands of living species, some familiar like our friend the goldfish, and a great many that are only familiar to dedicated disciples of fish science. For the time being, we hopefully can agree what a fish is.

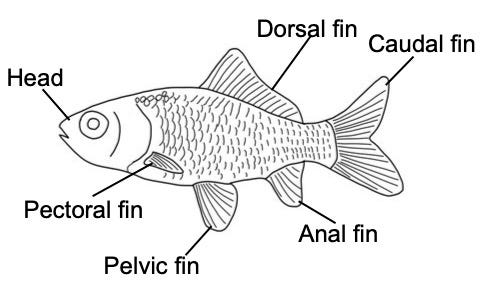

Now that we know what a fish is, we can learn the basic structure or anatomy of fish. Think of anatomy like a map. When entering a new area or land, it is best to have a practical map to avoid getting lost. The same is true when studying a group of animals. As anyone who has dissected or filleted a fish can tell you, their anatomy quickly becomes complicated. There are entire books dedicated to the subject (I recommend a few of my favorites at the end for further reading). For the time being, we are going to focus on the absolute essentials. Fish, like all other vertebrates, can be divided into a head, body, tail, and various appendages. The head contains the brain, eyes, ears, and a few other sensory organs that humans don’t have. The mouth and (in most fish) the jaws are also an integral part of the head, particularly for acquiring food. The head is attached directly to the body and shoulders, as fish don’t have necks. The body is a tube containing the major organs, including some familiar (the heart, digestive system, and other essentials like the gonads) and unfamiliar organs (the swim bladder, which acts like a scuba divers vest). The back of the body past the anus is modified into a flat, muscular tail. In fishes, the tail serves to propel the animal forward through the water through side-to-side motion. The appendages, called fins in fishes, primarily assist in locomotion. The pectoral and pelvic fins, one on each side of the body, stabilize the body and allow the fish to maneuver more precisely. The dorsal and anal fins, one of each, act like keels on the top and bottom of the body. These keels prevent fish from pitching and rolling as they swim through the water. The fins act in unison to move the fish through the water in a controlled fashion to pursue prey, escape predators, and navigate their environment. The changes in anatomy of the head, jaws, body, and fins over the history of fishes are critical landmarks for shifts in feeding and environment over time. Therefore, knowing these basic structures is essential to studying fish history.

Above: A quick guide to fish anatomy from our friend the goldfish. Line drawing by Jack Stack.

Our third and final tool is understanding how fishes change with time. Movies and television would tell you that time and natural selection have shaped some animals to be perfect at some role or ecology. Nothing is further from the truth. Any animal, including fishes, are not selected for a single role, or acted upon by a single biological process. Natural selection describes how some traits become more common in species because they confer some advantage in creating progeny. Any advantageous trait that cannot be passed down to children or does not lead to more children is invisible to natural selection. Species also change due to random chance (called genetic drift), the migration of organisms between populations, and genetic mutations. Therefore, the changes of natural selection will always be counteracted by chance, migration, and mutation, never reaching some perfect combination of traits. Also remember that any organism must perform multiple roles to survive. A fish must be able to gather food, to breathe, to breed, and to survive changes in its environment. Therefore, a fish’s traits must be able to perform multiple tasks and never are perfect for a single role or action. Although fish are wonderful animals that display a dizzying array of traits, none of them are perfect. These processes also mean that fishes do not stay the same, and over the deep history of the Earth they have changed as continents drifted, temperatures rose and fell, and other groups of organisms originated and went extinct. In the future, we will discuss this history and what means for the fishes we have today. Until then, thank you for stopping by.

Sources and reading on fish anatomy and evolution

1. Nelson, Joseph S., Terry C. Grande, and Mark VH Wilson. Fishes of the World. John Wiley & Sons, 2016.

2. Moyle, Peter, Joseph Cech Jr. Fishes: An Introduction to Ichthyology. 5th Edition. Pearson, 2003

3. Gregory, William King. "Fish skulls: a study of the evolution of natural mechanisms." Trans Amer Philos Soc 23 (1933): 75-481. Available at Biodiversity Heritage Library (https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/21482).